|

DVD/VIDEO REVIEWS

I lombadi alla Prima Crociata. Verdi. Teatro alla Scala 1984.

Conductor: Gianandrea Gavazzeni. Say what you will about the convoluted libretto of this opera, it features one of Verdi's

greatest and most arresting scores. The opera begins auspiciously enough with act one, in which Pagano pretends to atone for

the attempted murder of his brother Arvino – he loves Arvino's wife -- but is soon plotting his murder once more, and

winds up accidentally killing their father instead. The trouble is that this interesting plot expands to take in the Crusades,

mysterious hermits, an assault on Jerusalem, and a love affair between Arvino's daughter Giselda and the Muslin prince Oronte,

and there is no sign of a cohesive storyline. [In subsequent operas Verdi would learn to wisely focus on the love story.]

However, the music is consistently magnificent, practically one “hit number” after another, beginning with that

gorgeous chorus in act one on to Giselda's powerful denunciation of war in act two to Oronte's sensitive aria to Giselda from

the world beyond in act three to the several masterful choruses in act four – and more. Although Jose Carreras as Oronte

does indeed shout a lot, he also sings and interprets the role with genuine flair. Ghena Dimitrova has trouble with the high

passages and in general is not in fine form. Silvano Carroli gets better as Pagano as the evening proceeds, but Carlo Bini

is an unimpressive Arvino. William Schoell. NOTE: Schoell's biography of Verdi will be published in 2007.

MACBETH. Verdi. Deutsche Oper Berlin; 1987. Conductor: Giuseppe Sinopoli. This excellent production from Berlin of one

of Verdi's greatest achievements features some fine performances and highly dramatic singing. Renato Bruson is a nearly perfect

Macbeth and Mara Zampieri makes a compelling Lady Macbeth, although some may find her an acquired taste. Zampieri's voice

is quite distinctive, to say the least, rather powerful and at times quite shrill or, say, we shall, penetrating, but it certainly

works for this particular role, and her emoting is wonderfully effective. James Morris is quite strong, as usual, as Banquo

and Goetz Rose makes a solid Duncan. Sinopoli conducts the marvelous score with verve. Highlights include the act one duet

for husband and wife as they ponder the dagger and the fate of Duncan; the gorgeous ensemble that ends the act; Banquo's act

two aria with his son Fleance (portrayed very effectively by a boy supernumerary) at his side; the act two ensemble as Lady

Macbeth hovers over the prostate form of the guilt-wracked Macbeth; the great act four tenor aria; and the final chorus in

which everyone rejoices in the defeat of the wicked Macbeth. Top notch in all departments. William Schoell.

STIFFELIO. Conductor: Sir Edward Downes; Orchestra of Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. This is an excellent 1993 Covent

Garden production of a zesty, tuneful Verdi opera that was suppressed throughout his lifetime but finally rediscovered many

decades after his death. A minister comes back from a trip to discover that his wife, Lina, has been unfaithful. Duels, deaths,

accusations and recriminations follow, and whatever depth the characters have comes from the wonderful music. [The moral dilemma

posed by the murder is never actually explored.] This includes Stiffelio's “Dreadful thoughts possess me;” the

duet between Lina and her father Stankar; and the duel scene between Stankar and Lina's lover Raffaele in act one. In act

two we have Stankar's “Lina, I thought you were an angel,” and the glorious church chorus in the finale, not to

mention Stiffelio's aria “Our lives must follow different paths,” which boasts one of Verdi's most poignant melodies.

Whatever the deficiencies of his voice, Jose Carreras is dynamic in the title

role, sings with dramatic fervor, and acts well, too. Catherine Malfitano is in top from as Lina.

Gregory Yurisich makes an impressive Stankar, and Robin Leggate is fine as Raffaele. Downes conducts with vigor. William

Schoell

|

|

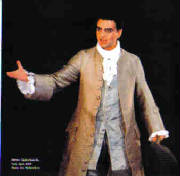

| Domingo in Queen of Spades |

QUEEN OF SPADES. Metropolitan Opera. The intimate approach of television helps tremendously to put over this somewhat

overblown Elijah Moshinsky production of Tchaikovsky's opera, with its large, sterile, framed sets by Mark Thompson; the opera

works much better on video than it did live at the Met. It doesn't hurt that it is well-directed both for stage and TV. Placído Domingo is superb as Ghermann,

whose obsession with a young woman drives him to acts of desperation and ultimate ruination. [This was around Domingo's 112th

role and his first in Russian!] Galina Gorchakova is also excellent as Lisa, the tortured object of his affections. Talented

baritone Dmitri Hvorostosky is solid as the Prince who loves Lisa; he is much more impressive on this

video than he was during the live performance. 71-year-old Elisabeth Söderström [the Met

called her back from retirement] is memorable as the elderly countess who holds the secret of the cards. The

other roles are all extremely well cast as well. There is much wonderful music in this opera (including a fair amount of Mozartian

pastiche), with the highlights being the ravishing love theme for Ghermann and Lisa [wonderful, pure, highly romantic Tchaikovsky];

Ghermann's beautiful act one aria “Heavenly creature, forgive me” [in fact the sequence

when Ghermann declares his love for Lisa is one of the Great Passionate Moments of Opera]; and the Prince's own moving declaration

of love for Lisa in act two. Valery Gergiev conducts with verve and sensitivity.

This is not a perfect Queen of Spades, perhaps, but it comes pretty close. William

Schoell

IL TROVATORE. Covent Garden. Conductor: Carlo Rizzi. Jose Cura (Manrico); Dimitri Hvorostovsky (the count); Veronica Villarroel (Leonora); Yvonne Naef (Azucena). With stark

but serviceable sets, this is a well acted and well sung – if not quite extra-special – production of Verdi's

great opera. Although Cura and Villarroel are undeniably good, they are somehow not quite as thrilling or outstanding as one

might have wished. Occasionally the tempo seems a little off, but otherwise Rizzi does a good job of conducting this lively

and often lovely score, highlighted by Manrico's act three arias, the Leonora/Manrico duet of act four, and, especially, the

magnificent Anvil Chorus. However, there are many other versions of this opera both on video and DVD and interested parties

should seek these out. -- William Schoell

LUISA MILLER. Opera De Lyon; 1988. Conductor: Maurizio Arena; Lyon Opera Orchestra. RM Associates/Public Media. A good

if not outstanding performance of Verdi's melodramatic, highly melodic tragedy is featured in this

video from Opera De Lyon. Luisa falls in love with Carlo/Rodolfo, the disguised son of the count,

who returns her feelings, but his father insists on a marriage of convenience to a Duchess. Rodolfo knows a dark secret from

his father's past with which he hopes to control him, but an unfortunate misunderstanding with Luisa leads to dire consequences.

June Anderson is very effective, if imperfect, as Luisa; Taro Ichihara makes a problematic Rodolfo.

Ichihara has a very nice voice and is a good singer, but the voice isn't quite big enough for Verdi and some of his high notes

are strained, to say the least. Eduard Tumagian (Luisa's father), Paul Plishka (the count) and Suzanna Anselmi (the Duchess)

are a bit more on the mark. Verdi had an excellent libretto to work from here and he responded with an equally fine score.

Especially outstanding pieces include the count's act one aria in which he sings how his son has brought him both love and

torment; Rodolfo's outcry of anguish over Luisa's alleged betrayal in act two; the chorus of maidens

who sing with pity of Luisa's sorrow in act three; the act three duet between Luisa

and Rodolfo; and the sublime trio (Luisa, Rodolfo, Miller) that provides the climax of the opera.

Conducted adroitly and with vigor by the hair-flapping Arena. Brigette Desnouses sings the solo part of the maiden's chorus

with lovely aplomb. -- William Schoell

L'AMICO FRITZ [Friend Fritz]. Pietro Mascagni. Jose Bros (Fritz); Dimitra Theodossiov ( Suzel);

Allesandro Paliaga (David). Conductor: Roberto Tolomelli; Cittalirica Orchestra. Kicco Video. Distributed

by Kultur Videos.

L'amico Fritz (1892) was composer

Pietro Mascagni's follow-up to Cavalleria rusticana, but is a light, charming

romance as opposed to a work of fiery, violent verismo, although the music can be very intense and passionate. Landowner Fritz

is nearly forty but loathe to settle down – to the consternation of his rabbi friend, David – who recognizes his

attraction to Suzel, the pretty daughter of one of his tenants and does his best to draw out those feelings. Suzel in the

meantime is in the throes of what she fears is unrequited love for Fritz. Fritz's jealousy is ignited when David intimates

that he is going to marry Suzel off to another man, but will Fritz rise to the occasion and take the plunge? In certain quarters

Mascagni has been criticized for writing “over-emotional” music for such a slight story, but although the plot

doesn't exactly concern the fates of Kings and Nations, it does present a valid emotional conflict and Mascagni responded

in appropriate musical terms. Fritz, a confirmed bachelor, must wrestle with feelings of loneliness and loss of freedom, a

complete change in lifestyle, while young Suzel is not only absorbed in the torments of First Love, but obsessed with worries

about what the whole course of the rest of her life will be – these aren't emotional situations? The scene in act three when they finally confess their love to one another will be very moving to any

one with an ounce of romance in their soul.

While it is great to finally have a DVD of this great opera, it has one

nearly fatal flaw. For inexplicable reasons, considering that L'amico Fritz is hardly a lengthy opera, the second half

of the famous “Cherry Duet” is completely cut. (One can only assume that there was some terrible glitch during

this section and the budget didn't allow for more than one taping.) Otherwise this is an excellent production, with tasteful,

traditional sets that serve the music and singers [instead of the other way around] and some very good singers who have a

decided flair for the material. The love duet in act three is even better than the Cherry Duet, and there are many melodious

and dramatic pieces in one of Mascagni's most memorable scores. This was produced at the Teatro di Livorno in Mascagni's home town in 1992. [It has a different cast and conductor

from the L'amico Fritz CD taped in Livorno the year before.] -- William Schoell

ROMEO AND JULIET. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden; 1994. Co-production with Theatre du Capitale, Toulouse and Opera-Comique,

Paris. Everyone in the cast gives their absolute all in this superb, very well staged production of Gounod's intensely romantic

masterpiece, conducted by Charles MacKerras. One will gain new admiration for tenor Roberto Alagna,

who sings and acts with great skill and really delivers on his major arias, such as the “what light in garden window”

piece in act two (one of the all time great arias of the 19 th century). As Juliet, soprano Leontina Vaduva has

a voice of uncommon beauty, and is also an excellent actress. Peter Sidham as Capulet and Robert Lloyd as Friar Laurence also

score, as does Anna Marie Panzarelli in her turn as the page boy Stephano – indeed the entire supporting cast is first-rate.

The opera itself is a melodic, romantic joy from start to finish, with several stunning arias and that gorgeous “coming

of dawn” duet in act four! If you want stuff like Einstein on the Beach and

The Death of Klinghoffer, you're certainly welcome to it, but let's face it

-- this (and Verdi, Wagner etc.) is the real operatic deal.

A recommended recording of this opera

features Alain Lombard conducting the Paris Opera Orchestra with Mirella Freni as Juliet and Franco

Corelli as Romeo. Freni's voice sounds beautiful on this disc. At first Corelli's too-liquidy voice, lisp and all, may be off-putting, but when he sings that great act two aria

you realize why this version is worth having. Corelli may not sustain the dramatic intensity of the final note, but this is

probably more a matter of style than due to any particular vocal or breath problem; his voice is big enough to handle verismo,

after all. -- William Schoell.

American Opera. Elise K. Kirk. University of Illinois Press.

Kirk takes us on an informative and entertaining journey from the early

days of opera in the United States up to the cringe-inducing works of Philip Glass and other minimalists. (According to Kirk,

“in today's currency” Glass got more money for composing The Voyage for the Met than Verdi did for composing

Aida.) She discusses many composers that have almost been lost to history, including several female and African-American

composers who were prominent in their day. She examines the trend toward verismo works among American

composers of the twentieth century, and looks into the different types of modern works that are currently appearing on our

operatic stages. Occasionally Kirk may be a little too “pc” in her assessments, but on

the other hand she tries to see the value in works that many of us may turn up our noses at. This is a fair, objective approach

to take. Besides, it is clear that her heart's in the right place when near the end of the book, slid neatly into a summation,

is a plea for composers to craft works that have memorable melodies and vocal writing, a lost art among most modern-day operatic

composers. An excellent book.

MALA VITA. Umberto Giordano. Bongiovanni. Maurizio Graziani (Vito); Maria Miccoli (Amalia); Paola

Di Gregorio (Cristina). Orchestra Lirico Sinfonica Della Capitanata. Conducted by Angelo Cavallaro.

Giordano may never have been quite in Mascagni's class (although his Andrea Chenier is a certified masterpiece) but he did compose a number of compelling and melodious operas, of

which Mala Vita (1892) is one of his earliest. This is an excellent, well-sung,

and adroitly conducted recording of the opera, which is another imitation of Cavalleria

rusticana. Vito is miserable with consumption and bargains with Jesus that if he is delivered from his suffering he will redeem

a wretched soul by marrying her. Shortly afterward he meets and quickly falls in love with the prostitute Cristina, who is

desperate to escape her life of poverty and debasement. Vito recognizes her as a soul he can save, but he reckons without

the sensual pull of his mistress Amalia, who is married to a friend of his. Amalia and Cristina have a confrontation, but

the former so awakens Vito's simmering passion that they sing a memorable duet before obviously hitting the sheets -- Cristina

is history. This, of course, does not bode well for Cristina's ultimate fate. Highlights include Vito's act one aria “O

Gesu mio d'amor” during which he prays to Jesus; and the soaring informal

duets for Vito and Cristina later in the act. Act two boasts Cristina's aria “Ma quest'amore e la unica.” in which

she declares her love for Vito to his mistress, as well as an attractive intermezzo. There is a rousing drinking/love song,

“C'anzon d'amor,” in act three, and the passionate duet for Vito and Cristina (“Buona

sera”) which leads into the highly sensual “Senti, Cristina.” If not exactly prime

verismo, the once controversial Mala Vita comes pretty close. -- William

Schoell

|

| Domingo, Caballe and Milnes record Giovanna D'arco |

CLASSICS CORNER

GIOVANNA D'ARCO. Verdi. James Levine; London Symphony Orchestra. Caballe; Domingo; Milnes.

EMI. Verdi's take on the story of Joan of Arc inspired nationalistic fervor among the Italians, who had to deal with Austrian

invaders the way the French had to put up with the English. The libretto has Giovanna's father, Giacomo, so morally outraged

at the thought that she might harbor impure feelings for the King-to-be, Carlo, that he denounces her as a witch and turns

her over to the British. Instead of dying at the stake, however, Joan dies on the battlefield, but not before a glorious and

bravura finale. The musical highlights include Carlo's act one aria in which he describes his vision about the painted statue

in the woods where he comes upon Giovanna; the contrapuntal act two duet for Carlo and Giovanna as he sings of love and she

sings of angels warning her away from it; the scene when Giacomo denounces Giovanna at the end of act two, which leads into

a beautiful trio with chorus [“No! Forme d'angelo'] as the three express their tormented thoughts; and Carlo's act three

aria in which he begs someone to kill him as he can't bear the anguish of Giovanna's death (prematurely announced). The music

as her not-quite-dead body is brought in and she then responds to the call of the angels etc. is Verdi at his best. This 1973

recording is superb, with Placido Domingo, Montserrat Caballe, and Sherill Milnes all at the top of their form. This is definitely

one of Verdi's lesser-known operas that should be performed much more often. --William Schoell

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS

THE KING AND I: The Uncensored Tale of Luciano Pavarotti's Rise to Fame by His Manager, Friend,

and Sometime Adversary. Herbert Breslin & Anne Midgette,

Doubleday 2004. “Uncensored” is right. Breslin, who was first Pavarotti's press agent and then his manager

for many years, will make few friends with this book, which is nevertheless a fairly juicy read. Breslin, who decided to part

company with his most famous client at the same time Pavarotti decided to do likewise [according to the book], depicts

the obese tenor as childish, spoiled, irresponsible, ungrateful, petulant, dysfunctional, undisciplined, and essentially,

a ninnie. Breslin nonetheless continually overrates Pavarotti's talent, claiming that he is a much

greater singer than Domingo, when every serious opera fan knows that it's just the opposite. (But then Breslin seems to think

that Angela Gheorghiu is a major talent.) He gives us the inside scoop on Pavarotti's rather pathetic

attempts to stay in the public eye, on the opera stage, and in the hearts of his many fans. Along the way Breslin bashes quite

a few former clients and others (in fact a more apt title for the book might be “Settling Scores”). One almost

has to admire Breslin for his total honesty, even if he reveals more of his own nature than he might have intended. Pavarotti

may certainly not be an intellectual, but he isn't entirely stupid either. When Breslin and co-author Midgette walk in to

interview Luciano, Breslin reminds the tenor that he's writing a book. Pavarotti points to Midgette and says, “No, she's

writing a book!” Score one for the Fat Man! Many of Breslin's other clients may bristle

at the fact that they're listed in an appendix in the book but mentioned nowhere else in the actual text. A good, fast read,

but take with a grain of salt. Although Breslin claims not to be bitter, it is unlikely that that is the case. -- William

Schoell

NOTE: As fans of opera often enjoy musical theatre as well, we're including this review on our opera page. THE

HAPPIEST CORPSE I'VE EVER SEEN: The Last 25 Years of the Broadway Musical. Ethan Mordden. Palgrave Macmillan; 2004. This is the latest volume in Mordden's excellent, intensely

readable series on the Broadway musical. Although Mordden writes in his introduction that this volume will be a “rant,”

he actually finds much to like in the last twenty-five years of musical theater, but he gets off some zingers now and then.

He lacerates the Tony Awards committee for nominating shows that have no real book (being through-sung), like Cats, for “Best Book” and other idiocies, and deplores the modern trend to put on

shows – often adaptations of movies -- that have little in common with the Broadway musical tradition. When discussing

the musical version of Ragtime, he's absolutely on target when he makes the

point that the character of Coalhouse would be considered little more than a terrorist, his actions excoriated, if he didn't

belong to a “pet” minority [“here's another dreary blast of self-hatred from the left.”] In the must-read

chapter “Junk is a Genre” he explains how serious musicals no longer stand a chance with a dumbed-down, much less

culturally-literate audience. “The New Stupidity,” he writes, “isn't just stupid: it's unchallenged. Intelligent

people have given up battling it because there's too much of it, and thus an absolute lack of knowledge becomes effectively

as valid as knowledge, innocent of shame. It points toward a society in which there is no reason to be educated at all.”

You won't always agree with Mordden, of course (which only makes the book more stimulating): Like many others I know who prefer

opera and serious musicals to Webber and stuff like Beauty and the Beast, I confess

I'm not as carried away with the talents of Michael John LaChuisa (Marie Christine) as Mordden is. But Mordden makes you want to give the particular musicals

he praises another listen. William Schoell.

Pietro Mascagni and His Operas. Alan Mallach. Northeastern University Press.

Pietro Mascagni: A Bio-Bibliography. Roger Flury. Greenwood Press.

Far from being a one-opera composer, Pietro Mascagni (Cavalleria

rusticana) was a figure of major importance in the musical scene of his native Italy during his lifetime. Because only

one of his operas remained an international hit after his death (with several others performed fairly often outside the U.S.),

the rest of Mascagni's impressive output was criminally undervalued. But now there are more performances of his other works

being scheduled at major venues, new recordings (all of Mascagni's works have been recorded, in fact), and a new appreciation

of the maestro's considerable talent. Flury's book is an excellent research tool which lists all of the articles and books

ever published about Mascagni, as well as virtually all performances of his individual operas along with detailed synopses.

I admit I was a bit taken aback when in his preface Flury oddly writes: “Mascagni must have been only too aware that

he lacked Puccini's melodic genius, sure theatrical flair and the ability to breathe life into his characters.” (!)

While Puccini may have been second to none when it came to melody (Mascagni was not exactly a slouch in that regard himself),

I completely disagree that Mascagni did not have theatrical flair -- and virtually every one of his operas proves that he

could breath life into his characters via his music. But everyone is entitled to his opinion, of course. Available at www.greenwood.com

While I also didn't agree with everything Alan Mallach

writes about Mascagni's operas in his excellent, long overdue biography, the book is a rich source of information about the

composer, his life and times, and his importance in the Italian musical scene. I hope the editors didn't chop too much out

of Mallach's manuscript. While reading, I had the sensation that Mallach had much more to say on different aspects of his

subject and I, for one, would have liked to have had it all available. (Of course, the publisher might have been leery of

a 1000 page book on Mascagni. Still, we can only hope the editing was done with sensitivity.) I could quibble that Mallach's

prose doesn't exude much passion considering the intensely passionate nature of his subject, but it's entirely possible he

felt such a treatment would be inappropriate for an academic publisher. Make no mistake, this is a serious biography and a fine one that finally gives the great composer his due. Lots of lazy writers over the years have

passed along the usual unfair and untrue tripe about Mascagni, but Mallach is anything but lazy. The book is a labor of love

and is highly recommended. Available at www.nupress.neu.edu.

It is interesting to note that Mascagni is treated with great respect in Mary Jane Phillips-Matz' excellent

biography of Puccini, which comes from the same publisher as Mallach's work. It, too, is highly recommended.

-- William

Schoell (You can read a revised, expanded version of Schoell's BBC Music Magazine

article on Pietro Mascagni at the excellent website www.mascagni.org.)

ONE MORE KISS: The Broadway Musical in the 1970s. Ethan Mordden. Palgrave Macmillan;2003.

Mordden capably surveys the best and worst of seventies musicals, with chapters on the contributions of Sondheim, the dawn

of “dark” musicals; off-Broadway offerings, “dreary” musicals that didn't work, and “don't”

musicals that should never been have conceived of let alone brought to Broadway. Mordden has done several volumes of these

books on musical theater (see above) and his “gay sensibility" has never been a problem, but this book, more than the

others, seems stricken at times not so much with a gay sensibility as a kind of out-dated, mean-spirited, “bitchy queen”

sensibility that adds nothing – not even humor – to the book. On one occasion, discussing a show whose cast was

mature, he makes remarks about the elderly which are meant to be funny but only come off as an expression of severe middle-aged

self-hatred. As usual, you'll find much to disagree with even as you're entertained by descriptions of shows you'd wished

you'd seen or are glad you missed. Mordden may be right that Company was a

startling new direction in musical theater, but it simply isn't that great a musical. He fails to understand that you can appreciate a certain work – or the works of a certain composer – yet still have your

own taste; it doesn't make you an idiot.

THE AMERICAN OPERA SINGER: The Lives and Adventures of America’s Great Singers in Opera and Concert from

1825 to the Present. Peter G. Davis. Doubleday, 1997. This thick, excellent volume exhaustively covers virtually every

American opera singer of note from the mid-19th century onward (with more of a concentration on older singers than more recent

ones, however) and a few others of less distinction. The careers and lives of such as Minnie Hauk, Emma Eames, and others

you may be completely unfamiliar with are chronicled in depth, with Davis looking at the strengths and weaknesses of their

voices as well as such factors as stage presence and personal problems that can lead to success or failure in this difficult

field. Lawrence Tibbett, Helen Traubel, Leonard Warren, Teresa Stratas, Phyllis Curtin, along with lesser-known singers, all

come in for insightful analysis, and there are the heart-breaking stories of Nell Tangeman, who was murdered, and Brian Sullivan,

who apparently committed suicide after a career downswing. Davis also looks at certain singers – Enrico Caruso, for

one – who were not born in America but who were claimed by the country as their own or who had some of their greatest

triumphs in the United States. Although there may be times when you may grow weary of the parade of obscure singers on display,

this is very readable, well-written, informative and for the most part quite entertaining.

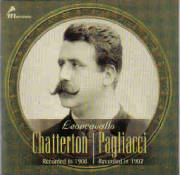

CHATTERTON. Words and Music by Ruggiero Leoncavallo. Conductor: Leoncavallo. Marston. Thomas Chatterton was an eighteenth

century impoverished poet of genius who committed suicide when he was only eighteen years old. Leoncavallo was exactly that

age when he decided to write and compose an opera loosely based on the poet's life, but while there was an earlier production,

it didn't really hit the stage with any success until 1896, four years after the premiere of Leoncavallo's masterwork Pagliacci. Chatterton is not in the same league, but this classic recording of 1908 makes clear that it is an interesting,

noteworthy work that deserves a modern-day recording. The sound quality of the disk is rather amazing considering the recording

is nearly one hundred years old, but one cannot, of course, get the full flavor of the orchestra or voices, or indeed, the

opera itself. Still, some of it is a pleasure to listen to, and tenor Francesco Signorini is a singer in the grand tradition

who gives full and proper intensity to Chatterton's persuasive arias. [Tenor Francesco Granados sings

the role of Chatterton on some of the tracks, but he is much less impressive, although hardly terrible.] Chatterton not only

has to deal with extreme poverty, but with what he thinks is his unrequited love for his married landlady, Jenny (a creditable

Ines de Frate). As in Massenet's Werther, the main theme of the opera is suicide,

which hangs over nearly every note. The highlights include the fairly well-known aria “Tu sola a me rimani a poesia,”

Chatterton's desperate monologue in which he realizes he has nothing in the world to give but his art; his friend Clifford's

admonishment to an unresponsive Jenny (“Perche severa e rigida sempre”); Henry's (Jenny's young brother) charming

reading of a sad bible story (“D'acqua e di pane”); and Jenny's beautiful aria in which she wishes for happiness

for Chatterton (“Benedetta dal ciel per sempre sia”). The third act has particularly good music and includes a

fine duet between Chatterton and Jenny as they finally express their love for one another. The ending is perhaps more melodramatic

than moving, but the music is always effective. Good singing actors could probably bring more life to the characters than

Leoncavallo does in his otherwise well-crafted libretto. -- William Schoell

ARTICLE

GIACOMO PUCCINI (1858 - 1924) is now acknowledged by most as one of the greatest operatic composers

of all time -- but it has taken the musical establishment an awfully long time to (grudgingly) admit it. Part of the problem

was that Puccini had never been considered one of the "immortal" composers because he wrote almost exclusively for the operatic

stage instead of the concert hall. Then there was the fact that his music was too "beautiful." How can such "pretty" music

have substance? wondered those who found Puccini's work more emotional than "intellectual." But it's in this very emotional

element that the brilliance of Puccini's music can be found. Take, for instance, the scene in Madama Butterfly when

Sharpless, the American consul, tries to find the words to tell young Cio-Cio-San that her husband, Pinkerton, who has been

gone for three years, has taken an American wife and will never return to her in any concrete fashion. "Would it be such a

tragedy if you were never to see him again?" he asks the young woman (or words to that effect.) Suddenly the music soars with

a violent, powerful crescendo of intense, magnificent sound and Cio-Cio-San runs into her house to come out with the

three year old child that neither Pinkerton nor Sharpless were even aware of. She doesn't have to say anything: Puccini's

music gets across her desperation, fear, hope, even rage, as she holds up the child so that Sharpless can see for himself

that, yes, it would be a tragedy if her beloved Pinkerton, the father of the boy, never returned to her.

There are other great highlights in his operas: the group of gold prospectors gathering money in La fanciulla del

West so that one of their number, a sobbing, lonely, homesick boy, can afford to return to home to his mother.

Cavaliere des Grieux singing that spectacular aria in act one of Manon Lescaut, a piece that is as full of the rhapsodic

joy of young love as it is of the despair that des Grieux's love for Manon will eventually engender. And then there's

Turandot's song about how her ancestor was abused by men and why she beheads any would-be suitor who fails to give the correct

answers to her three riddles. And the moment when Rodolfo pours out his anguish over Mimi's health and welfare to Marcello

in La boheme as, unbeknownst to him, Mimi listens and realizes she is dying. Even his lesser-known operas like

his first, Le Villi (which illustrates that Puccini had The Gift right from the get-go) and his second, the intense,

almost "veristic" Edgar , have wonderful moments and memorable music.

Puccini was one of

the most romantic and sensual of all composers. (The love duet in act one of Madama Butterfly is the perfect musical

expression of the night of physical passion that awaits Pinkerton and Cio-Cio San, constructed -- not to put it too crudely

-- as one ascending "orgasmic" wave after another. Of course this was deliberate on Puccini's part. Who says operas are stuffy?)

Opera singers who do not have Puccini in their repertoire may become stars, but they can't become superstars, because Puccini

-- one of the most popular, if not the most popular of all opera composers -- gives them the opportunity to thrill the audience

with intense, soaring arias and duets that require skilled, passionate, expressive, and powerful voices. (Paging Mario Del

Monaco and Renata Tebaldi!)

Puccini did not write the libretti for his operas, but he worked closely

with each librettist and was a master of dramatic stage effects. Unlike his contemporary, friend (and rival) the incomparable

Pietro (Cavalleria rusticana) Mascagni, Puccini did not experiment or vary his style much, which is probably why be

became so successful (in general, audiences do not want "something different" from their favorite artists), but he was a consistent

master of melody, mood and showmanship. Certain modern-day Broadway composers have been heavily influenced by Puccini (Andrew

Lloyd Webber lifted from Fanciulla del West for “Phantom of the Opera” for example), but they haven't his

degree of skill, technique or talent. In a way its strange that so many people will go see all-singing no-dialogue Broadway

shows which are really ersatz, (inferior) operas, but they won't go to the Metropolitan Opera to see the real thing! In other

words, go see “Rent” (the rock musical allegedly inspired by La boheme), if you must, but make sure you

see Puccini's original masterpiece, too. (Better yet, just see La boheme!) ... the opinionated William Schoell.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Villazon Does It French Style |

ROLANDO VILLAZON. Arias: Massenet; Gounod. Evelino Pido; Radio-France. Virgin.

I wasn't overly impressed with Villazon's debut CD [see below], but found myself admiring the

tenor – with reservations – on this collection of arias by Jules Massenet and Charles Gounod. Villazon's voice

still isn't quite as rich as other tenors, his vocal peculiarities include some strain and quiver and can be shrill, but it

is also capable of great sweetness, as well as a decided power and intensity. Generally – and this is probably what

his fans most respond to – he sings with a great depth of feeling that really puts him over on most of these

tracks. Like other tenors, such as Roberto Alagna, who try to make a big initial splash with the Italian and verismo repertoire,

Villazon's voice proves much more suited for the French style and this CD offers many pleasant moments. His breathy softness

contrasted with vocal power is very effective on the second aria from Werther, which he sings beautifully and with

great expressiveness. In the first of two arias from Romeo and Juliet Villazon's voice caresses the listener and he

manages to deliver nicely on the high notes, although he kind of flubs the last one, which is a bit unpleasantly pinched.

He sings the pants off a little-known aria from Gounod's Queen of Sheba and does full justice to a piece from Massenet's

Le Mage, which is a very lovely aria to begin with. In addition to more well-known arias from Manon, Le

Cid, and Faust, there are also gems from lesser-known operas such as Massenet's Roma, Griselidis, and Le roi

de Lahore, and Gounod's Mireille and Polyeucte. The orchestra is in top form, each aria conducted with verve

and polish. Villazon's almost hysterical fans will cherish this CD, but I warn others that while you will certainly admire

the tenor, you may not find that his signing delivers that certain extra-special thrill that all of us tenor enthusiasts

are hoping to hear. But he is decidedly a talent. William Schoell

|

| Mexican tenor Rolando Villazon |

ROLANDO VILLAZON. Italian Opera Arias. Conductor: Marcello Viotti;

Munchner Rundfunkorchester. Virgin.

Now here's a problematic tenor: is he merely the latest Andrea Bocelli-like

poser, or an outstanding operatic talent? The record company that's hyping him, and his fans – influenced by the hype

– would have you believe the latter, but his voice is simply too thin to be as impressive as one might hope. Although

some fans have raved about his high c in “Che gelida manina” from

La boheme, it is hardly a “whopper,” but rather shrill and strained. In fact, in most of these arias Villazon comes across merely as an average light lyric tenor who is often out of his element. While he initially

sounds fine doing the bel canto repertoire, upon further study even these pieces are troublesome.

On the other hand, his singing is expressive and his voice, despite that frequent strained quality, attractive enough. He

even manages to deliver on “E lucevan le stelle” from Tosca, singing with power and commitment. But on

certain pieces, such as “La mia letizia” from I lombardi, you're all too aware

that he is simply not doing justice to the piece as say, Neil Shicoff, could. Don't be fooled by the

hype: Villazon is talented but he is not “the fourth tenor” and he does not in any way, shape or form sound like

“a young Domingo,” as some have claimed. In an earlier period when there were a dozen or more world-class

tenors, someone like Villazon probably wouldn't have made it to the Met. It is interesting that the notes that come with

the CD discuss the arias but say absolutely nothing about Villazon's voice or background. Viotti conducts,

and the orchestra plays, with admirable vigor. In addition to several Donizetti, Puccini, and Verdi pieces, the CD also includes

two lesser-known Mascagni arias from L'amico Fritz and Nerone.

-- William Schoell

BATTLE OF THE "VERISMO" TENORS

Recently a couple of contemporary tenors have tried their hand at the type of material normally handled by such

stentorian vocalists as Placido Domingo and the even more stentorian Mario Del Monaco. There was a time when there were any

number of tenors who could sing the verismo (and Verdi) repertoire with great panache and skill, but nowadays you can count

such gentlemen on one hand. How do these new fellows stack up?

Contender A: Jose Cura

VERISMO. JOS É CURA. Philhamonia Orchestra. Conducted

by Jose Cura. Erato.

The ambitious Cura not only sings on this CD, but also conducts

the orchestra. While the big sound of verismo opera doesn't necessarily come naturally to Cura, the tenor really works at

it and in general hits the mark. When I first heard Cura (on a live CD of Mascagni's Iris

recorded at the Rome Opera), I admired his handsome, plummy sound but was disappointed in his lack of vocal heft. (It didn't

help that Domingo had also recorded this opera.). I had the same problem with his all-Puccini CD, and even when he was live

at the Met where he performed in Cavalleria, his debut at that house. It's

not that Cura was by any means bad (and he is an excellent actor), but that he wasn't any better than the less-hyped tenor

who sang in Pagliacci. Therefore I approached his recording of verismo arias with a certain skepticism. True, Cura does not have the massive,

hyper-dramatic sound of a Del Monaco (who does?), but through effort, skill and a lot of hard work he manages to sound quite

good and often excellent on many of these tracks, and he deserves credit for even tackling this difficult material in the

first place (there aren't many modern-day tenors who would). At first you assume he's employing an almost baritonal

sound for the first track, the prologue from Pagliacci, because this number

is traditionally sung by the baritone, but this interesting darker sound continues throughout the album. His “vesta la giubba” is full of a great depth of feeling, and he really delivers on both the arias from

Andrea Chenier, where his interpretations are both powerful and sensitive.

His performances of the Cavalleria material are expressive and dynamic. He

gets all the drama out of the aria from Mascagni's Lodoletta and his handling of the piece from the same composer's Guglielmo Ratcliff is impressive. His voice shows a little strain at times, but he generally manages to hit and sustain

his high notes. His conducting is first-rate, showing a real appreciation of, and flair, for this material. [Some may argue

that his tempi are a little slow, but this almost always seems to be effective.] Along with all the traditional classic verismo

pieces, he includes a few rediscoveries of Mascagni's, as well as lovely pieces from Catalani's Loreley and Giordano's Marcella. Both the aria from Frenchetti's

Germania and Cura's performance of it are fairly spectacular.

Whatever you think of Cura, he does have a distinctive sound and he gets an A plus for effort. While it's a question if Cura

could sustain an entire live performance of, say, Ratcliff at this point, it

must be said that this is a man who is hard-working, takes risks, and is clearly serious about his art. -- William Schoell

Contender B: Roberto Alagna

NESSUN DORMA. Roberto Alagna. Arias. Conducted by Mark Elder; Orchestra of the Royal Opera House,

Covent Garden. EMI.

Alagna's record company did the tenor little good, giving him far more

hype than he – or virtually any modern-day tenor – could live up to. Like Cura, Alagna

is not really a verismo-type singer a la Del Monaco -- the CD focuses exclusively on post-Verdi Italian

composers -- and the results are even more mixed than with Cura. To be fair, Alagna is certainly not a bad singer. His voice

often sounds quite good and he can be extremely expressive on certain tracks, such as the highly dramatic aria from Zandonai's Giulietta e Romeo. He gives good performances of arias

from La Wally, Turandot, Leoncavallo's Zaza and I zingari {aka Gli zingari}. But his recording of “Amor ti vieta”

from Giordano's Fedora is completely unimpressive, and while he can hit his

high notes with some security, they never really have that extra-special zing and occasionally they even sound

a mite strangled. At times Alagna's reasonably attractive sound is marred by a very unattractive and raspy strain that borders

dangerously on bleating. [This is more apparent when you listen without headphones, which – like microphones –

can hide a multitude of sins.] All in all, this is less successful than Cura's

verismo attempt, although it will not be without its pleasures for Alagna's legion of casual

opera fans. There are those who feel Alagna is much better singing French operas such as Romeo and Juliet and

I concur.

AND THE WINNER: MARIO DEL MONACO

|

| The stupendous Mario Del Monaco |

VERISMO. Mario Del Monaco. This is a collection of arias taken from various (generally full-length) recordings from the

early fifties till mid-sixties, therefore they vary in quality. One thing that is clear from the first is that Del Monaco

was a tenor of the first rank, with a voice that was born to handle Verdi and Verismo without the

slightest strain. This is not a tenor who shouts – his voice is so naturally big he doesn't have to (“he could

put Placido Domingo in a tooth cavity” as someone put it). He has a dramatic intensity and vocal

power that leaves one breathless (but not Del Monaco). In other words, unlike Cura and Alagna, he

doesn't have to work at it (or at least he doesn't sound as if he does.). He gives a splendid rendition of “Amor

du vieta” from Fedora and an astonishingly powerful

performance of an aria from Zandonai's Giuletta e Romeo.

He is at the top of his form with the two pieces from Cavalleria and is superbly

expressive on “Vesta la giubba” from Pagliacci. He gives a thrilling interpretation of

the act one aria from Andrea Chenier, and a sublime performance of the famous

act four aria from that same opera. His performance of the two arias from Adriana Lecouvreur are exciting and intensely emotional, as are the two pieces from Catalani's La Wally. He sings with vibrant, controlled abandon on the aria from La gioconda (although with a darker, deeper tone than usual), and puts over the two arias from Mascagni's Isabeau as few contemporary tenors could. Tracks from the mid-sixties,

such as an aria from Leoncavallo's version of La boheme, are less satisfying

but hardly poor, and Del Monaco is hampered during the prologue from Pagliacci

by employing the traditional baritonal approach. It's his ringing high notes that are the tenor's trademark, not the lower

register. There may have been tenors with prettier or sweeter voices (Jussi Bjorling,

for instance), but few who had Del Monaco's force, persuasiveness, and unparalleled dynamism. One may admire the likes of

Alagna and Cura when they attempt this material, but it is only Del Monaco who truly thrills. -- William Schoell.

A BIT OF BROADWAY

PASSION. Stephen Sondheim. James Lapine. Presented on Live at Lincoln Center.

Musical Director: Paul Gemignani; American Theatre Orchestra. This is a superb concert version of the Sondheim musical that

originally played on Broadway and appears to have a script that has been revised for the better. [While it solves some problems

it creates others, but let's not quibble.] Michael Cerveris is Giorgio, who is having an affair with the married Clara (Audra

MacDonald) but becomes friends with Fosca (Patti LuPone), the homely cousin of his superior officer. The two form an intellectual

bond but Fosca falls hopelessly in love with Giorgio. At first he is completely unable to return her feelings – until

he realizes how much he really means to her and how much she means to him. The three leads are simply excellent, with LuPone

not only forcefully singing her role but making Fosca more sympathetic than usual. Cerveris is a much more sensitive Giorgio,

mining all the emotional undercurrents of the role with aplomb and singing with vigor. Audra MacDonald has a less showy part

but both her singing and acting are exemplary. Richard Easton and Allen Fitzpatrick also score as, respectively, the doctor

and Colonel Ricci. The production is well-cast down to the smallest parts. While this does not appear to have been released

on VHS or DVD, it is worth seeking out on public television. The fully staged version with the original Broadway cast is also

excellent and is available on DVD. The music is too “popular” for this to be classified as serious opera, but

the damn thing does grow on you, doesn't it? William Schoell

JANE EYRE The Musical. Music and Lyrics by Paul Gordon. Book

and additional lyrics by John Caird. This is one of the better opera-influenced musicals of recent years, although the music

is more of the pop ballad persuasion than operatic. The songs move along the story and enrich the characterizations in an

admirable way, and in general the score is romantic and tuneful [and a hell of a lot better than Jane Eyre: The

Opera]. Forgiveness is a hymn of near-masochistic

bent, with an interesting, downbeat melody, sung by Jane's pious young friend who dies. The housekeeper Mrs. Fairfax (brilliantly

played by Mary Stout) is given two excellent patter-type songs: Perfectly Nice (“Did

I have a point? I can barely recall”), and A Slip of a Girl, in which

she renders in comical rhymes her distraught, amazed reaction to learning that Jane and Edward Rochester are engaged. In As

Good as You Rochester relates how his background and romantic tragedies have affected

his nature. Blanche Ingram, who hopes to wed Edward herself, celebrates art and culture and his need for a wife in Finer

Things. Jane decides that she herself has a future with Edward in Painting

her Portrait, and the two woman both sing of Robert – separately -- in the pretty

"duet" In the Light of the Virgin Morning. Rochester declares to Jane “You

are my second self” in The Proposal, and sings a vigorous Farewell

Good Angel, after she learns the truth about his marital status. Brave Enough

for Love is the climactic love duet, although it is topped by Sirens, which might be called a fighting-their-way-to-love duet. After Sirens, the best song in the show might be Gypsy, with its funny lyrics and

snappy melody, in which an impersonator gives suspect readings to a number of women and reveals all their secrets. In this

original Broadway cast CD, Maria Schaffel sings Jane and James Barbour sings Rochester and both are excellent. Conducted by

Steven Tyler. Sony.

CLASSICS CORNER

UN BALLO IN MASCHERA. Conductor: Dimitri Mitropolos; Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. Live 1955 Recording (Oct. 12th).

Monaural. Even the small roles are played by name singers in this excellent recording of one of Verdi's greatest – and

grimmest – operas, which has one of his darkest and most memorable scores to go with its excellent libretto. No less

than Marion Anderson sings the role of the seeress Ulrica, who predicts death at the hands of a friend for King (aka Count)

Riccardo. Riccardo is sung by the stentorian and dramatically effective tenor, Jan Peerce,

who really delivers on the act three aria “Na se m'e forza perderti,” in which Riccardo accepts that he must forever

part from the woman he loves. This woman, Amelia, is sung by Zinka Milanov, who can be a bit shrill at times, but does a very

nice job in her major aria “Morro – ma prima un grazia,” in which she begs to see her child before she dies.

If that weren't enough, Robert Merrill is the recording's stand-out in the role of Renato, who just happens to be Riccardo's

best friend – and is married to Amelia! Merrill gives a thrilling delivery of the great aria “E sie tu che macchiavi”

in which he sings of his torment at this most ultimate of betrayals – wife and best friend -- and vows to destroy them

both. Giorgio Tozzi has the small role of conspirator Samuel, James McCracken appears (all too) briefly

as a judge, and Roberta Peters displays her very beautiful voice as Oscar, the King's messenger, in the charming short aria

“saper vorreste.” The most famous piece in the opera is from act one, when Riccardo (with chorus) urges Ulrica

to read him his fortune (“Di' tu se fedele”), but there are other outstanding pieces, such as when he and the

chorus react to her prophecy of doom (“E scherzo od' e follia”), and the wonderful chorus, based on the cadences

of laughter, that ends act two (“Ve' se di notte qui”). This is a great recording of a great opera, one of the

genius Verdi's finest achievements, and a genuinely moving experience as well. -- William Schoell

|

|

|

|

|